Supply chain transparency in the jewelry industry is more challenging than in most industries. Unlike the mining done for commodities like oil — which typically involves massive investments by large corporations — mining for jewelry materials is commonly done by artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM). These miners — now estimated at more than 40 million worldwide — work alone or in small family or community groups or (more commonly in Latin America) in small companies. They tend to work off the grid, by hand, without technology, and with very little economic representation in the industries, they sell to. According to Cristina Villegas of Pact, “About 20% of all gold is mined this way, 20% of all diamonds, and 80% – 90% of colored gemstones.”

Colored gemstone miners rarely get fair market prices for their efforts

Transparency in gold pricing makes it possible for gold miners to keep around 80% (on average) of the London Bullion Market (LBMA) fix. But colored gemstone prices are highly variable, so it’s difficult for gemstone miners to know what to charge. This means that colored gemstone miners rarely get fair market prices for their efforts. Furthermore, colored gemstones are typically sold in the rough (unimproved) state, and shipped (most often to other countries) to aggregators of raw materials who heat, cut, and polish the gemstones. At that point, it’s difficult to tell where the materials came from and what conditions they were mined under.

Added to that complexity is the fact that, unlike the materials used in other industries, reuse of jewelry materials is common. Precious metals and gemstones routinely remain in circulation for hundreds of years; easily reused, re-manufactured, and re-sold to create new pieces.

For consumers asking where their jewelry materials came from, it is not just difficult . . . it is often impossible to say. Jewelers who want to work with only responsible materials have discovered that sourcing them is very challenging. The dictum trust, but verify is problematic for even large corporations with significant financial resources. Traveling to artisanal mining sites, creating systems for tracking, and adding value closer to the point of extraction is all very expensive, time-consuming, and sometimes dangerous. What is difficult for large corporations to accomplish is often completely out of reach for small businesses. And yet, the worldwide fine jewelry industry is dominated by small business.

Supply Chain Initiatives Often Too Complex, Inaccessible, for Small Business Application

The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), established in 2003, was a first step in addressing the problem of conflict diamonds in the jewelry supply chain. KPCS is often criticized for being flawed, and it is. Formed as an initiative by the United Nations General Assembly, it includes 82 member countries – along with all the politics and conflicting priorities that entails. KPCS continues to evolve, and it plays an important role in keeping conflict diamonds on the radar of government leaders. But its impact gets smaller the closer the diamonds get to market. Why? Because small business owners in the jewelry industry are required to ask their suppliers to confirm in writing that they are compliant with KPCS, but they have no meaningful way to verify or validate the responses.

The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) was formed in 2005 to create standards and certifications for jewelry practices. The standards extend to nearly all jewelry materials, and address human rights, labor rights, environmental impact, mining practices, and product disclosure. Becoming certified is an extensive process, and involves self-reporting. Most small businesses do not have the resources (time, administrative capacity) to fully certify, but RJC makes its standards and self-assessment tools available for free, and there is some evidence that more small business owners in the jewelry industry are accessing those tools and starting their own journeys toward responsible supply chain practices.

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Just start somewhere.

Like KPCS, the RJC is often criticized for its flaws. But as Stewart Grice, VP of Mill and Refining for Hoover & Strong (a metal refiner and manufacturer and leader in ethical metals supply) said at the 2018 Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference, “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Just start somewhere.” The work KPCS and RJC have done to create standards and define practices is extensive, and can be considered a good start.

Bringing Responsible Supply Chain Activism to Smaller Jewelry Companies

In 2006, around the same time that RJC was forming, three independent metalsmiths — Christina Miller, Susan Kingsley, and Jennifer Horning — founded Ethical Metalsmiths. Their intention was to bring awareness of abuses in the jewelry supply chains to smaller jewelry producers and consumers, and to develop a market for metals and gemstones that were sourced in accordance with international standards. They also focused on jewelry making practices at the level of the small jewelry shop, to create awareness of the environmental impact of fabrication techniques and explore more responsible ways to produce jewelry and run small jewelry businesses. This was the first grass-roots responsible jewelry practices movement, and the association became a nexus for like-minded jewelry practitioners, many of whom are thought leaders in the responsible jewelry movement today.

What was needed, and has finally begun happening in earnest, was to create connections between on-the-ground mining resources and practicing jewelers. The recently launched Moyo Gemstone Collaboration represents excellent progress in this regard.

A Model for Future Responsible Jewelry Initiatives?

The Moyo Gemstone Collaboration offers an exciting model for short supply chain initiatives in which small businesses can participate. It demonstrates that it is possible to closely connect artisanal miners and jewelry makers, and it marks an important shift in the efforts of small-scale jewelers to create meaningful, verifiable responsibility initiatives.

The challenges to creating responsible supply chains and transparency in the jewelry industry are big, messy, and global. It’s easy to look at the situation and think, “why bother? There are too many variables, too many problems. It’s too hard to create change.” But projects like the Moyo Gemstone Collaboration shine a bright light on the process.

Less than 3 Years from Spark to Market

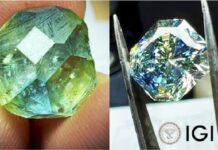

When the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) approached Pact in 2016, they wanted to know if providing gemstone education to those who mine the gems could make a difference. Pact, which works to assist artisanal and small-scale (ASM) mining communities, responded enthusiastically. A pilot project involving GIA trainers, Pact staff, and the Tanzania Women Miners Association (TAWOMA) was launched. That project provided the education necessary for the women miners to begin getting much more value for the rough gem material they mined; earning the miners three-to-five times more than they had been earning before.

Then, at the 2017 Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference, the project evolved. It was there that Cristina Villegas of Pact, Monica Stephenson of ANZA Gems, and Stuart Pool of Nineteen48 met and formulated a plan to advance the collaboration with TAWOMA. They envisioned a direct, short supply chain between TAWOMA and gemstone buyers and cutters. To create traceability they brought in Everledger as a blockchain technology partner, and they have worked very quickly since then to co-design the project with the miners themselves.

Big Idea, Targeted Focus

Within three years, this project went from idea to education to trace-ability to market, and is incorporating the same blockchain technology that multinational logistics companies use to track movement of inventories. Instead of trying to do this project in an industry-encompassing way, they focused on a specific group of miners. In this way, they were able to pilot a project that could be reproducible, in full or in part, in the future. This focused, rapid project methodology will deliver fast feedback for improvements. It is reasonable to expect that improvements can be made quickly, due to the relatively small group involved in the collaboration.

Inclusion and Collaboration

The Moyo project is a model of cooperation that brought miners, community activists, cultural experts, educators, market experts, and technology providers together to hash out the details of a mine-to-market initiative that will benefit all the participants. Business strategists are keenly aware that highly collaborative projects with great diversity of thought and experience are the most likely to be successful. This is even more true when it comes to projects that cut across business, cultural, and national boundaries.

Flexibility

Expansive projects like KPCS and RJC are necessary and important. But large, political, corporate efforts also come with inherent flaws. For the same reasons that multinational corporations often struggle with innovation and entrepreneurialism, multinational initiatives are often beset with politics and inertia.

The Moyo Gemstone Collaboration, with its smaller team and tighter focus, is less likely to experience those shortcomings. There is no guarantee that the project will escape politics and prove to be adaptable, but limiting the number of potential agendas certainly makes that more likely.

Rapid Feedback

One of the biggest challenges to any change initiative is that we don’t know what we don’t know. At some point, a new idea must be launched, and feedback collected. Small initiatives like Moyo are typically more effective at collecting and acting on criticism and suggestions, and rapid feedback loops are key to leaping ahead quickly in a project’s learning curve.

One of the complaints heard recently in the jewelry industry is that there are too many different initiatives, and that the initiatives are not all coordinated. But we already know the limitations of concentrating such important work in the hands of very few, very large, efforts. On the contrary, the industry has probably suffered from a dearth of such projects in the past, and the recent surge in initiatives is a sign that meaningful progress could be around the corner.

In fact, there are a number of similar, exciting projects being led today by small collaborations. This is good, because the jewelry industry is still in its infancy in creating responsible supply chains, and it must move quickly to catch up to and get ahead of consumer expectations. The more minds we can bring to the table, the faster we will figure out how to “do gooder,” as Mark Hanna, CMO at Richline Group (and a leader in corporate social responsibility initiatives in the jewelry industry) likes to say.

The Moyo Gemstone Collaboration offers real, meaningful progress now. But perhaps its greatest legacy will be as a template for future initiatives. At this point in our progress, the industry should not be holding out for perfect solutions. Instead, it should be working quickly and with great intention to explore the methods, partnerships, and collaborations that will solve the biggest problems in the simplest manner. As those projects are launched and tested, industry knowledge, engagement, and commitment will grow. And that may be the only way to solve big, messy, global problems: one community and one initiative at a time.

NewsSource: forbes

Disclaimer: This information has been collected through secondary research and TJM Media Pvt Ltd. is not responsible for any errors in the same.